Selected Essays

On Becoming One Hundred

Everybody thinks it’s a great achievement to live to be one hundred. It’s as if you’d won a triathalon or one of those super-grueling foot races that takes twenty-four hours. You get your picture in the paper sitting in your wheelchair at the old folks’ home surrounded by beaming staff and family members whose smiles look a bit like grimaces while you’re straining to blow out a big candle on a cake they’re holding beneath your chin. Everybody out in the world seems to be convinced it’s a goal we should aspire to. Somebody’s bound to ask to what do you owe your blessed longevity. Down at the place where my Dad was living, they even have a club – The Centenarians – for such high-achievers, and their names are inscribed onto a plaque hanging in the dining hall. (People still think it’s a big deal even though according to a website devoted to these long-livers, the U.S. has about 72,000 available for worship and admiration at the moment.) If you’re going about out in the world escorting one known to be a centenarian, you’ll hear, “One hundred! My, how wonderful! Congratulations!” followed most usually by a personal anecdote about how Auntie made it to 101 or even 103 and could still manage to water-ski and divide 347 by 13 without using a calculator.

About a month ago, I was pushing my Dad in his wheelchair down a hallway in the facility where he lived, just to get him out of his room. He was about one week short of 100. In marathoner’s terms, he’d supposedly passed the “despair” stage of miles 18-22 and had slogged into the “exhaustion and elation” stage where the finish line is either literally or figuratively in sight. As we turned a corner, we rolled up onto a group of visitors being led about by a marketing director. The group looked to be about a half dozen members of the same family, one alert, early-elderly fellow in a wheelchair and his fully ambulatory wife, accompanied by adult children and spouses. When the saleswoman spied us, I could see it all in a flash in her eyes: my Dad’s very popular with residents and staff, known for witty banter and good cheer, and she’d spied an opportunity to make a little innocent use of him as a living endorsement of the facility’s beneficial practices and judicious selection of clientele.

“Well, here’s Bill!” she gushed. “People tell me you’re about to be one hundred! How marvelous!”

“One hundred?” crowed one visitor. “Wow!”

Then two women from the group rushed over to pat his shoulder; one kissed him on the forehead. The other bent down into his face and declared, “One hundred! Mercy! What a wonderful, wonderful blessing!”

He looked right at them and said, “Please somebody just give me a pistol so I can shoot myself.”

Work Habit

Recently I saw a trailer for the cable show “Black Gold” featuring oil-drenched roughnecks working on a rig, huge boulders of metal swinging wildly like cockeyed pendulum weights about their heads, and I realized that I’d gone my life without proving myself by doing this particular job.

You might ask why does that matter?

While clearing out a drawer, I found a report card from my ninth grade Civics class. On the back were five subheadings under the title “Work Habits” – 1. Works in Class; 2. Use of Materials; 3. Pride in Work; 4. Initiative; 5. Following Directions.

Apparently learning good “Work Habits” was deemed essential to a child’s education in the 1950s, and we were given one of three grades: S for Satisfactory; I for Needs Improvement; and U for Unsatisfactory. I seemed to have had good “work habits” -- in all subcategories save one I garnered a steady row of Ss.

In “Following Directions,” during one grading period Mr. Green thought I Needed Improvement. I don’t recall what caused him to mark me down; knowing myself now, I probably decided that my way of doing something was better than the method he proposed to the other students. But I do remember vividly how this wounded me. After all, I was someone who showed Pride in Work. My poor mark seemed to say that he disapproved of me, and winning approval was the very point of learning good work habits. “Pride in Work” didn’t mean simply that I took care in completing and presenting projects, didn’t do something slapdash: it meant that my very willingness and ability to work were themselves sources of pride, apart from any particular assignment. I had pride in the process as much as in the product.

PUMPING IRON

Don’t spread it around, but I love to iron. Every Sunday evening when the 60 Minutes clock starts ticking, I haul my folding board out of the hall closet, mantle it upright about five paces from my television set, get out a week's worth of shirts, trousers, and jeans (ironing jeans is an old cowboy tradition), and press the bejesus out of everything while Ed, Morley, Harry, and Mike yammer away ; about problems far more serious than wrinkled fabric, and far less easily remedied. Talk's the cheap coin of information there, so it takes only an occasional glance from the board to the screen—say, when I'm flipping a sleeve—to keep up with what's going on.

I'm not the only man who irons: I know a Pulitzered photographer who braved the fire in El Salvador (credentials for machismo seem necessary here), and he gets fifty cents for every blouse of his girlfriend's he irons. (He works too cheap.) One academic dean of my acquaintance does the smoothing, as it once was called, for his wife and son. Three cases may not constitute-a trend, but it's obvious that the distaff half of the global population has forsaken this old, joyous craft. Like so much of our work done by hand, it has fallen into disfavor. It's linked with domestic slavery; of all the household chores once designated as women's work, ironing seems to have been the most odious, so it now carries the most trenchant political overtones. You don't ask a woman to iron a garment for you (even if you've found one who knows how) any more than you might request that she greet you at the door in a rip-off French maid's costume, a martini in hand and your slippers in her teeth.

FAUX HAUBEAUX

We all loved being poor. My college pals and I drank Gallo’s Paisano wine, $2 per gallon jug. We drank the cheapest brand of beer, Grand Prize, though our mentor, an English instructor, made his own which we drank as if it were the tastiest mead from blessed bee honey and none of us could admit it tasted like a skunk’s bath water.

We relished our martyred indignation when we saw rich kids tooling about campus in cars their parents had bought them, when we passed the best restaurant on the square and saw them coming and going. We believed our deprivation was a sign of moral superiority. We stewed in our righteousness. We detested “fat cats,” Wall Street BigWigs, corporate tools and fools, General Motors, yachts, private golf clubs, banks and bankers, sororities and fraternities, cheerleaders and the jocks they cheered on, “fine” wines and those who cared about them, any event requiring a tuxedo and a ball gown, evangelical television preachers, “fascists” of all stripes, the Ku Klux Klan, the House Un-American Activities Committee, most all things Southern (except, of course, Delta blues), the FBI, society orchestras (Lester Lanin, Guy Lombardo), fancy food dishes with foreign names, the industrial-military complex, make-up on females and hairstyles requiring professional maintenance, all advertising, the business diploma and those who pursued it, the novels of Ayn Rand and Jacqueline Susann and their fans – and probably a thousand other items, now long since forgotten, all composing a nexus, a gestalt, about money, about chasing after it and using it to yield power over poor people such as ourselves.

Look Back In Anger

I could call the cops, beg them to shoot Larry, but they probably wouldn't. Larry lives right across the alley; I think of him as a George Romero movie prop because I have killed him so many times, and yet he lives. And barks. His barking just ripped me out of a cozy dream for the second night in a row, and now I lie trembling, teeth and fists clenched. I am furious.

Last week I tried to do something about it. Larry's only a dog, so I called his owner. He said, "Hey, he's a dog, he's gonna bark. You gotta expect that. It keeps the burglars away."

He was wrong; Larry the Labrador's barking does not signify anything useful. He cries, "Wolf! Wolf. Wolf!" I've stood in my yard at noon, my work interrupted, and watched this animal yowl at passing cloud formations. Squirrels blink a block away and it drives him berserk. If he's taken inside to be hushed up, invariably he will be let out at 5:00 a.m., at which time he will scream, "Hey! Anybody else up yet?"

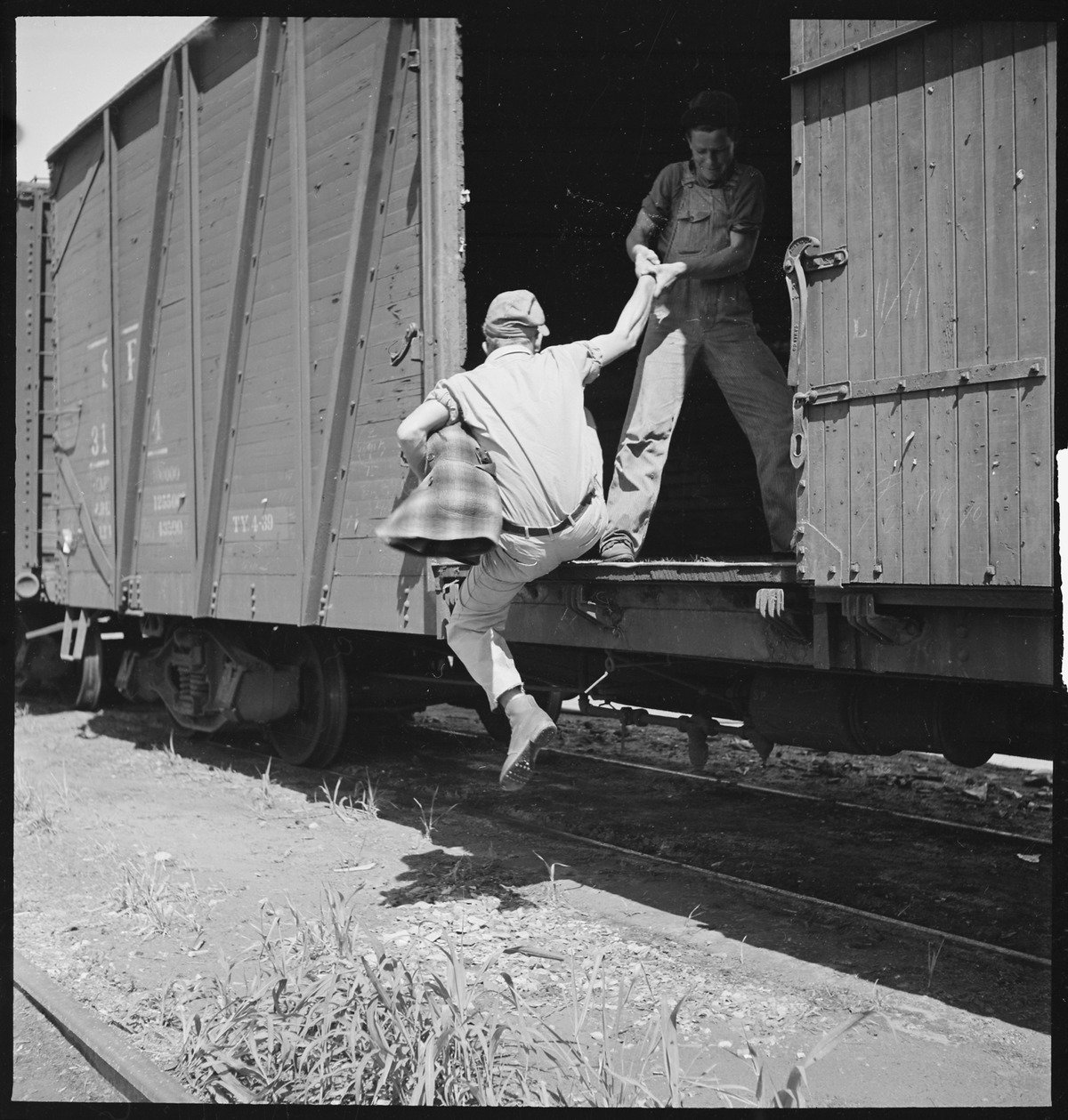

image USC Santa Barbara Current

A Mother’s Day Meditation

Some big old lunky boy sits on the sidelines in helmet and pads looking pretty glum about the score, but when the camera zooms in on him, he looks up, grins, and what are those words he's mouthing?

Kill 'em? Remember the Alamo? Coke adds life?

Of course not. He's saying, "Hi, Mom!"

Every man is always a sonny boy to his dear old mudder, but before we wax too dewy-eyed over this eternal maternal bond, We should remember that familiarity breeds, if not contempt, at least a loving skepticism and unerring knowledge: Nobody truly knows a mother as does her child. So when my writing students whine that they don't know anything to write about, I pull out my "My Mother Never" exercise and simply assign them to finish that phrase.

This does inspire kindly thoughts of mom, but the depictions of her are always tainted with a leathery tang of the actual, proving the eye of the child, no matter how loving, is never clouded. Here, for instance, a son describes his mother's struggles over cooking:

"She once told us that she would rather scrub the johns in a filling station than prepare a dinner for five. Last year, she was going to start a new tradition of preparing Christmas dinner. Of course, she burned it — that was sad, since the only preparation needed was for her to warm an already cooked ham we got from a neighbor. If it weren't for restaurants, my sister and I would have starved to death."

Muddling Along in French

Among the problems American-born WASPs face is that sooner or later they are required to speak a language they were never required to learn. Growing up in a cattle town in New Mexico in the 1950s, the closest I ever came to a foreign tongue was when I ordered enchiladas in our town's sole Mexican restaurant and when I watched Pepe le Pew cartoons. To my innocent way of thinking, courses in Latin, French or Spanish were about as necessary to my curriculum as homemaking or art.

Naturally, at the time I never dreamed that one day I'd be sitting in a cafe across from the Louvre trying to tell a sly French waiter why I could not possibly have ordered the washtub of beer he and another waiter lugged out to my table and planted under my nose. I never knew then I'd have such a trenchantly vivid suspicion that I was being snickered at, or that I'd be wishing I hadn't believed studying foreign languages was silly "because you never use them." What I didn't know then was that foreigners use their foreign languages about 99 percent of the time, and if you're wandering among them, it's very helpful to be able to avoid saying, "Please see to it that I walk away from here with ice cream on my head" when you actually mean, "Give me a roast beef sandwich on whole wheat, light on the mayo."

My Dad and Donald Trump

My Dad was also a womanizer. Except he just wasn’t very good at it. He was more of a “one-womanizer.” He fell in love with my mother in high school, where she was the Class Poet and he was the Class President. One summer before they were married they were separated because he was working in the hills of Tennessee tramping from one farm to another selling Bible concordances. He wrote letters harassing her. . I love you, I love you. I love you, I love you, I love you. Do you love me? This isn’t a bit clever. I’m tired: “My head aches, and a drowsy numbness pains my sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk or emptied some dull opiate to the brain” Keats – Ode to a Nightingale. Cost Uncle Charles $126 for me to learn that, so why not use it? Please, please, don’t let anything in the world change your plans about coming home Sun. I’d much rather be talking to you now than writing. First, I’d tell you how crazy you are. Then I’d tell you how glad I am. Then my shy, boyish way how much I care.

Too bad that he was stuck with this one woman, who stayed married to him until she died at age 87 after they’d been wed for 63 years. Sad. Loser.